REFUGEE BLUES

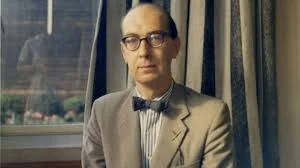

WYSTAN HUGH AUDEN

Wystan Hugh Auden (1907–1973) was a student and later a Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. One of the most important poets of the century, he has published several collections of poems noted for their irony, compassion and wit. Although a modern poem, ‘Refugee Blues’ uses the ballad form of narration.

Say this city has ten million souls,

Some are living in mansions, some are living in holes:

Yet there’s no place for us, my dear, yet there’s no

place for us.

Once we had a country and we thought it fair,

Look in the atlas and you’ll find it there:

We cannot go there now, my dear, we cannot go there

now.

In the village churchyard there grows an old yew,

Every spring it blossoms anew:

Old passports can’t do that, my dear, old passports

can’t do that.

The consul banged the table and said:

‘If you’ve got no passport you’re officially dead’;

But we are still alive, my dear, but we are still alive.

Went to a committee; they offered me a chair;

Asked me politely to return next year;

But where shall we go today, my dear, but where shall

we go today?

Came to a public meeting; the speaker got up and said:

‘If we let them in, they will steal our daily bread’;

He was talking of you and me, my dear, he was talking

of you and me.

Thought I heard the thunder rumbling in the sky;

It was Hitler over Europe, saying: ‘they must die’;

We were in his mind, my dear, we were in his mind.

Saw a poodle in a jacket fastened with a pin;

Saw a door opened and a cat let in:

But they weren’t German Jews, my dear, but they

weren’t German Jews.

Went down the harbour and stood upon the quay,

Saw the fish swimming as if they were free:

Only ten feet away, my dear, only ten feet away.

Walked through a wood, saw the birds in the trees;

They had no politicians and sang at their ease:

They weren’t the human race, my dear, they weren’t

the human race.

Dreamed I saw a building with a thousand floors,

A thousand windows and a thousand doors;

Not one of them was ours, my dear, not one of them

was ours.

Went down to the station to catch the express,

Asked for two tickets to Happiness;

But every coach was full, my dear, every coach was

full.

Stood on a great plain in the falling snow;

Ten thousand soldiers marched to and fro:

Looking for you and me, my dear, looking for you and me.